The trial of Faithful and Christian is one of the most graphic episodes in Pilgrim’s Progress. We are introduced to a range of new characters: Lord Hate-Good, Envy, Superstition, Pickthank, and a jury so stacked against the cause of Christ and the good of the Church that there can be no doubt as to the verdict that will be returned to the Court. Again, part of Bunyan’s purpose is to underline that consistent reality that the world hates Christ and His Church without cause (Ps.35, 38:19, 109:3, 119:86, John 15:25 etc.). This is bizarrely comforting if for no other reason than when we speak of and live for Christ, and incur the displeasure, hatred or anger of others, we can often turn inward, wondering what we did wrong, or perhaps what we didn’t do right. Painting the Judge, Witnesses and Jury in such vibrant colours helps us to see that the reason can lie not in us, but in those who pit themselves against the Gospel.

It is worth noting in passing that not everyone in Vanity Fair stands so implacably against the Pilgrims, nor are they so determined to engineer their demise. But enough are, and few enough are willing to seek to prevent it. Yet ‘the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church’. When our testimony to Christ is sealed with tears and blood, our evangelism resonates with the chords of creation, and people are saved. Later, as Christian leaves the Fair with Hopeful (one such convert), we are told ‘there were many more of the men in the Fair who would take their time and follw after’.

The Pilgrims are accused of being enemies of the Fair’s trade, causing commotion and division, and winning ‘a party to their own most dangerous opinions’. In a sense they can only plead guilty! The first witness, Envy simply reiterates that they were evangelistically zealous, and that they had declared that ‘Christianity and the customs of our town of Vanity, were diametrically opposite, and could not be reconciled’. Again, there is little the Pilgrims could dispute, but Bunyan’s point is that persecution can be motivated by Envy. He draws this from the Scriptures where we see the Pharisees treatment of Jesus, and then later the Apostles being driven by their resentment of growing impact and popularity (see e.g. Matt.27:17-18, Acts 13:44-45, Phil.1:15-18). No matter how sophisticated the charges brought against the Church, they are often a cover for more base motives. In Acts we see that fear of losing profit is enough to instigate a riot against visiting preachers (Acts 9:23f)!

Superstiton is the most dangerous of the witnesses, and perhaps the one drawn most acutely from Bunyan’s own experience. He has in mind the clerics of the ‘official’ religion, who can often be amongst the most vicious persecutors. We need to be careful here for the reality on the ground is often complex and varied, but in many contexts where the Church is persecuted, there is an ‘official’, institutional ‘Church’ that is nominal, liberal, puppet to the state, and compliant with the dominating culture and political opinions and dynamics of the day. Again, we need to take great care against sweeping generalisations, for there are often many genuine Christians in such denominations, but Bunyan’s point is that the denominational structures can often be brought to the service of persecuting believers. That was his own experience, with Anglican Bishops of the day at the forefront of Bunyan’s own mistreatment. There is nothing like the preaching of the true Gospel to invoke the hatred and hostility of pretenders, even when by his own confession ‘I have no great acquaintance with this man, nor do i desire to have any further knowledge of him'.

The third witness, Pickthank, is the most obscure to us. It’s an archaic word that speaks of someone who will do whatever it takes to curry favour with those he perceives to be in power. He isn’t driven by any personal offence taken, but he knows that the nobility of the town are feeling threatened, and so adds his voice to the prosecution in the hope of winning their appreciation, acknowledgement and acclaim. He will ‘pick’ on the pilgrims to gain the ‘thanks’ of the nobility.

Faithful’s defense comes down to a restatement of the Gospel, and a re-commiting of himself to the mercy of God. There is no question of justice being done, and the Judge instructs the jury that Faithful’s crime is apparent, that by his own mouth he has confessed to treason and that he deserves to die. There is of course, the judge continues, legal precedent, for the world has persecuted the Church to death since the days of ‘Pharaoh the Great, servant to our prince’.

The Jury’s verdict is a foregone conclusion, and Faithful is ‘presently condemned, to be had from the place he was, to the place from whence he came, and there to be put to the most cruel death that could be invented’.

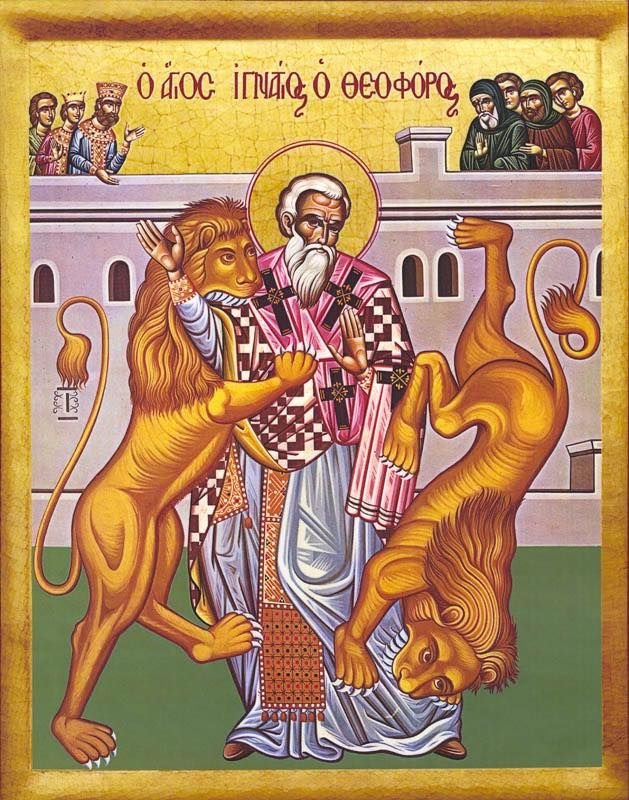

‘Thus came Faithful to his end’.

Which we might mis-interpret as a tragedy, a disastrous miscarriage of justice, a denial of Faithful’s basic human rights. But as we’ll see tomorrow, Bunyan paints a different picture.

Questions to ponder:

What mistakes could the Church / Christians make in seeking to avoid persecution? Do you see those mistakes being made today?

Do you think that the British Church’s unwillingness to suffer, and her lack of evangelistic effectiveness are linked?